|

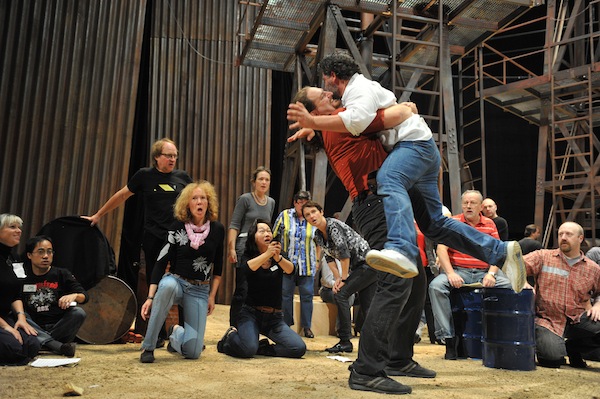

In 2007, Teatro Colón was closed while it was refurbished; as a result, the Samson et Dalila performances were held as concert productions at Teatro Coliseo. While not an optimum singing environment, José Cura lifted the staging to a different level with his remarkable charisma and singing.

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “The absence of a full staging leaves the voice as principal, though not the only tool to feel each of the multiple states of mind. And in this sense Cura surpassed the others with his brilliance. Flirting with some overacting but never actually doing it, Cura applied an infinite number of vocal devices to his singing, with overwhelming artistic excellence. Thus, Samson sighs agonizingly in the lamentation of the third act and his singing is perfectly audible and touching, he harangues the Hebrews almost like a Wagnerian tenor or demonstrates all his doubts in front of the lurking Dalila with an inevitable musical conviction. The first delights came when the choir, prepared by Salvatore Caputo, began from an imperceptible, perfectly tuned pianissimo, and advanced in increasing volume and intentions to build a fugue shaped with enough freedom by Saint-Saëns to allow the Hebrew slaves to sing of their despair. And when from the center of the choir, hidden among so many dark clothing, there arose the powerful, overwhelming and magnificent voice of José Cura, there followed astonishment, fascination and wonder.” La Nacion, 25 June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “[T]he most significant aspect in this case didn’t seem to be the general concept but the expressive determination of tenor José Cura, overwhelming even when not “acting.” Cura established the drama from the “get go”, when he appeared in the middle of the choir and began to address his people simply with a look. It was evident that the limitation of the staging reflected even greater significance on the most minor inflection. Cura admirably personifies his role, as much through his acting as through his vocals. His line of singing is luscious, without cracks in the heroic registry in the first, as in the more lyrical of the second or in the whispered and broken of the third.” Clarin, 25 June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “As to José Cura, he convinced me by the end of the performance. After a start in which he offered a very personal interpretation, one that continued until the beginning of the third act, he made a turn and frankly managed to convince me totally as an actor and as well as with his vocal delivery, emphatically projecting the drama to come and the fate of Samson and this is where I point out that without a doubt the first (two) acts are more José Cura than Samson but the third is Samson winning over José Cura and that is the key to his triumph.” La Opera BuenAyre, August 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “If a musical event depends on the presence of a great artist on stage, that is what happened with Camille Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila. The tenor José Cura, in the main role of this masterpiece of French opera, was incomparable. His vocal qualities are exceptional, his musicality ideal and the force of his delivery impressive. To this it is necessary to add his charisma. Samson has an ideal interpreter in Cura and this was demonstrated in the concert version in the Teatro Coliseo. It was not a concert in the traditional sense, but a ‘staging within a space,” as it was called, that reflected Cura’s lack of inhibition and his unconventional approach. Cura was the pillar of this Samson and Dalila.” Ambitoweb, 25 June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “In the remarkable opening performance of this concert version programmed by Teatro Colón, José Cura, stunning vocally and also profoundly convincing as an actor, clearly demonstrated the significance of space in heightening the dramatic effect from the start in his manner of interacting with the chorus. With powerful yet subtle voice, Cura took delight in the pianissimos, in lightening the voice, and even in groaning. His character literally took body and his voice became part of that body.” Pagina/12, 25 June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “José Cura as Samson was impressive. From the initial scene, in which he emerges from the rows of the choir, his volume and commitment were captivating. In the first act he favored the use of subtlety, in the second he shaded his expressiveness to show his love, and he reached his best moments in the beginning of the third act with his concentrated painful expression and singing in a highly pleasing mezzo voce. It is possible to agree or not with his way of expressing and with some of the tricks of a singer with such solid experience but it is impossible to stay indifferent to his singing and artistic expression.’ MundoClasico, June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “The indisputable star of the night was José Cura. From his initial appearance, almost magical, materializing in the middle of the chorus, singing as he came down the stairs to the edge of the stage, the adrenaline raced through the auditorium. His voice sounded marvelous, with excellent volume, beautiful timber—almost baritonal—the particular emphasis he put on his statements and the incredible array of vocal resources that he used. And his work as an actor carried his unmistakable stamp. Samson seems to fit him like a ring on a finger. The quality of his contribution did not waiver through the performance and he received a well-deserved ovation. Cura really is a Divo, with all this word implies. Everything with him is grandiloquent but without doubt he is one of those singers for whom every phrase, every sound he emits has a special value, a bonus.” Canto, August 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “The possessor of significant volume, solidly dramatic, the Rosarino tenor arrives in the middle of a career that has taken him to the most distinguished international stages. And this is certainly absolutely justified, based on the qualities he demonstrated in his performance in the concert version of this most beautiful work, so rich and harmoniously creative, Samson et Dalila. Cura (Samson) highlighted a powerful dark tone, full of color, very supple in nuances, completely homogeneous and expressed with astonishing naturalness. And though conceptually he exaggerated somewhat his rage and the vocal contrasts of the characters (he is brave and strong in the first act…blind, weak and reduced to servitude in the last), his work showed without doubt that he is one of the principal singers of the world at the moment.” La Prensa, 25 June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “José Cura, in the role that perfectly suits his histrionics on stage and which he was profusely and brilliantly represented, had to adapt to [the concert platform]. Undoubtedly, he maintains his charisma intact, his voice powerful, and his interpretation of this Judge of Israel converted in a warrior leader looking for his people's freedom is simply magnificent.” Ópera Actual, September 2007

|

|

José Cura Para Ti Julieta Mortati 10 July 2007

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpts] “There's classical music that's a bore and popular music that's brilliant." The renowned Argentine tenor, based in Madrid, starred in the opera Samson et Dalila at the Teatro Coliseo in Buenos Aires. In a conversation with Para Ti, he explained that he studied music, martial arts, and even took bodybuilding classes to survive. He began singing at age 27 because "I discovered that with my voice I could pay my bills." He is considered one of the best voices around the world for his interpretive quality. José Cura (44) traveled to Argentina to be present at his parents' golden wedding anniversary (the celebration is on Saturday, 7 July in Rosario, his hometown). He was accompanied by his wife, Silvia, and his three children: José (19), Yazmín (14), and Nicolás (11). His visit, initially secret, soon became known, and the family plan was interrupted by five performances of Samson et Dalila (by Camille Saint-Saëns) in the Teatro Coliseo, with the artistic staff of the Teatro Colón, in Rosario with the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Monument to the Flag and with a chamber concert commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Mozarteum, where he will give the world premiere of the cycle Sonnets (on July 8), composed of seven pieces based on poetry by Pablo Neruda. In his last week in the country, he walked around with dark circles under his eyes and a runny nose. "On stage, it's freezing," Cura says about the Teatro Coliseo, "and it's not just the cold, there's even wind! Yesterday my shirt was flying off, and the choir boys were on stage wearing scarves and shawls. We held on, but in the end, my body said 'enough.'" What did it mean to sing in Buenos Aires? “Well, singing for your people and your family isn't the same as singing for people you respect because they're your audience but you don't know them; you don't know who's on the other side of the lights. When you sing in your home country, you know that there are people in the audience who knew you from your childhood.”

During his childhood, Cura learned to play the piano intuitively, watching his father play Beethoven and Chopin at home. He later studied guitar, composition, and piano, and enrolled in the School of Art at the University of Rosario. At the age of 12, he began conducting choirs and orchestras. In between, he specialized in martial arts and played rugby. At 27, he began singing. “Singing appears quite a bit later in my musical career. I discovered I had a voice and at first, the investment very logical: with this voice, I'd be able to eat and feed my family more easily than with songwriting. As harsh as it may sound, I got into singing for purely economic reasons,” he admits, explaining: “Then, what started as a blind date ended up in a lifelong relationship, but at first, I thought I'd sing for a few years to make ends meet, save some money and pay for my house. Eventually, it became a full-time profession that transformed me into who I am. There's a thing called 'destiny' and things just happened the way they were supposed to happen. I can't complain.”

And when things went wrong, he didn't complain either. In 1983, he wanted to enter the Teatro Colón, and a teacher told him during an audition: “You don't sing, you shout.” He then taught tae kwon do and bodybuilding classes and worked in a hardware store. In 1990, he auditioned again at the Colón University and was finally accepted. He decided instead to go to Europe. With his wife—whom he met when he was 16—and José, his first son, Cura took a Pan Am flight to Milan. A stubborn man… “I was always very stubborn. Like children, who every time they get up in the morning no longer care about anything that happened the day before and just go out to play again. I think that's how it is. I was convinced that I had something to say, that I was ready to say it, and that I would keep going until someone finally listened to what I had to say, and that someone would pass it on to others. It's being eternally a child despite all the mistakes and setbacks. It’s what makes you want to keep going.” In 1995, he won the Operalia competition, chaired by Plácido Domingo, and gradually became one of the most prestigious tenors in the world, praised by critics for his performance quality. A year later, he debuted as Samson at the Royal Opera House in London, a role he continues to perform to this day and for which he received the Orphée d'Or and Echo Klassik awards. –How important is it for you to perform Samson et Dalila? –One of the most touching things about opera is its relevance. Just as 1,500 years before Christ people killed in the name of God, the same thing is happening 3,500 years later. Human beings still lack the courage to take responsibility for their own mistakes or successes. If we need to kill, we blame others, and if we kill in the name of God, all the better, because no one can rant or say anything to him. –And personally? –This opera has a particular aura because it's accompanied me practically throughout my entire career. I've worked it out, studied it, thoroughly studied it, and thoroughly sung it. The character is the same in every work; the equation is different. Each performance is like an act of love, a sexual act, and the audience in front of you is your partner in that moment. And they have to ask themselves: "How much did I give to the artist?" The difference between an audience that surrenders to the artist and one that doesn't is enormous. It's like making love to the person you love or doing it with a plastic doll. - I have a particular affection for this opera because it has accompanied me practically throughout my career. I have it very done, very chewed, very studied and very sung. Each performance is like an act of love, a sexual act, and the audience in front of you is your partner at that moment. And they have to ask themselves: “How much did I give to the artist? The difference between an audience that gives itself to the artist and one that doesn't is enormous. It's like making love with the person you love and doing it with a plastic doll. -How do you prepare for a performance? -The voice works like a model's face. When you plan to do a photo session, you try to sleep as much as possible to look as “wrinkle free” as possible. And on the day of the performance, a singer tries to rest as much as possible so that the voice is as fresh as possible. That’s ideal. –Why did you stay in Europe? –I like Madrid. We have a beautiful house where I am able to indulge in all the things I’ve wanted to indulge all my life, all my whims. – Divo tasts? Eccentricities? –I have no eccentricities. But I do indulge myself the way I want. I have my wine cellar at home, a ton of wines I'm collecting. I have my pool, a gym, things I've always wanted to have and in the way we like best. He confesses that when he's alone at home, he prefers to enjoy the silence and that he never sings in the shower. He likes shopping, cooking, and drinking wine. –You also like photography. –Yes, I love it, and now we're negotiating my first photography book with a Swiss publisher. I like photojournalism, not posed photography, going out on the street with my camera to gather stories from all over the world. I like to grab my camera and get lost. I've been in rough neighborhoods and have had to be rescued from difficult situations more than once. I love getting to know the true face of the people. –Opera is considered elite. Is there anything about that that bothers you? –There's always been talk of the elite but anywhere in the world, a ticket to hear opera costs less than a ticket to a stadium. For many years there was a trend: people who liked classical music wanted to feel more exclusive. That's stupid because the music was written by composers for everyone. This tendency to deify them is a fad from the early 20th century, when these divisions were created for the same purposes that all divisions are created for: "Divide and conquer." When in reality, there is good music and there is bad music. There is classical music that is boring and popular music that is brilliant. |

|

|

|

Samson was a terrorist Clarin 22 June 2007 Sandra de la Fuente

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

The last time he appeared during the Colon season was 1999. Tomorrow José Cura will perform Samson et Dalila in the Coliseo. He reflects on the work….

After an eight year absence, the Rosarino tenor José Cura returns to Buenos Aires in Camille Saint-Saëns’ opera Samson et Dalila which, in concert version, will be presented in the Coliseo as part of the Colon’s season. Recognized as one of the great voices on the international stage, José Cura is a rare artist who, besides singing, also conducts orchestras, composes, and has recently taken on the role of director.

In spite of his established reputation as a singer in major venues around the world, he has been elusive with the Colón. Besides his Otello in 1999, he has hardly performed in the theater. “My absence coincided with a turbulent time in this country. During this period, the Colón did not have a consistent program, which complicated hiring artists who book their calendars five or six years in advance. The question they always asked me was ‘Can you be here the day after tomorrow?” explains Cura in an exclusive interview with Clarion. Finally, when Marcelo Lombardero took over, the Colón became more stable, especially in its approach to the outside. ‘During the great crisis, the Colón was spoken of as a theater to which it was better not to come. Now European musicians are beginning to say it is worth the trouble of coming to the Colón.’

Who wins and who loses in the concert version of Samson?

All operas lose in concert version; when drama is lost, the opera can lose impact. But Samson et Dalila is very much an oratorio, so it is less strange [in concert] than if it were verismo. But in this production, we will not be stuck like stakes behind lecterns and neither will we be wearing tuxedos. Though there is not much staging, we will enter and leave according to what we are singing, there will be dynamics, gestures, and lighting that will give us a certain atmosphere.

What is your idea of Samson?

I believe there are two ways to interpret the role. One is consistent with the prophetic Samson, the good Christian. This vision seems to me to be in error. Samson was a judge and in his time, judges were military leaders. They defended the town and subdued others: in essence, they were violent, revolutionary men. Samson killed as if he was breaking a piece of bread. He killed a lion with his own hands and pulled down a temple, sacrificing himself. With that act, he became the first terrorist in history. He killed in the name of God—a contradiction—and was sacrificed in the name of God. His legend is more than 3500 years old and sadly it is still scandalous today. My vision has been criticized many times because they say it is not spiritual. Certainly, it lacks the spirituality of today but it represents the spirituality of 1500 years before Christ when an eye for an eye was still the law.

It is difficult to accept that such an aggressive personality can be in accord with the music of this opera.

There lies the danger. One must interpret the text, not the music. The music adorns the text, but that decoration needs be used to extract advantage. Used well it can be very interesting because the beautiful music contains a text that is tremendously cynical. The Return of José Cura

La Nueva 23 June 2007

[Excerpt] Tenor José Cura compares his character Samson with Ernesto "Che" Guevara BUENOS AIRES (Télam) - The tenor José Cura compared his character Samson with Ernesto "Che" Guevara, in reference to Camille Saint-Saëns opera-oratorio Samson et Dalila which he will perform with singers Cecilia Díaz and Luis Gaeta under the direction of maestro Rodolfo Fischer as part of the 2007 season of the Colón.

|

José Cura, the Return of the Prodigal Son La Nacion Cecilia Scalisi 22 June 2007

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt] One of the highlights of Buenos Aires' current classical programming is, without a doubt, the return to the country, after an eight-year absence, of one of its prodigal sons: the Rosario-born tenor José Cura. Having lived in Europe for 16 years (currently in Spain), his name is synonymous with success for dramatic roles in the operatic repertoire. This naturally makes him one of the most sought-after tenors in the world and one of the most popular figures in his field. And it's no wonder when, in addition to a phenomenal voice, José Cura boasts the appropriate physical presence for these types of roles and an exceptionally complete and multifaceted professional background. The arrival in Buenos Aires of one of the most dazzling stars of international opera will mark the Teatro Colón's season with the stamp of the best in the world of opera, in a role tailor-made for him: the character of Samson, in the romantic opera Samson et Dalila by Camille Saint-Saëns. In a concert version, together with Cecilia Díaz, the cast, choir, and orchestra of the Teatro Colón, the tenor will perform tomorrow at 8:30 p.m. at the Coliseum.

The titan of the OperaIn his fifteen years of successful international career, José Cura has not only frequented the most prestigious halls and theaters of the classical world (Met, Covent Garden, La Scala, Opera National de Paris, Staatsoper of Vienna, Hamburg and Zurich, Deutsche Oper Berlin, among others), but has also visited countries far from the traditional circuit, conquered exotic audiences for opera and tirelessly took the art of music and theater to unthinkable corners of the world. The most glamorous divas sing at his side and the most famous conductors have directed for him. Parallel to this intense activity in the theater (as an orchestra conductor, singer and régisseur), he exploits with surprising ease his broad qualities of communicator and showman, offering recitals and shows—some of them on open air stages for thousands of people—in which he has combined singing with orchestral direction (in an original format that he himself called "half and half"), which has earned him both the criticism of the most conservative sectors of the musical medium and the admiration of his audience—and an unusual popularity for an artist of the classical world.

When José Cura began to be mentioned on the covers of the world's musical publications, the figure of the legendary Samson was one of the most immediate and appropriate references associated with the name and image of the Argentine tenor. Not only because of the qualities of the timbre and the character of his voice but also the exuberance of his personality, the charisma and imposing stage presence announced that Cura would be (among other great characters that he embodied with equal empathy, such as Otello, Canio, Don Carlo) the ideal interpreter of the biblical hero for several generations. Since then, years have passed and, unlike what often happens with careers that happen too quickly and with excessive grandiloquence are launched and ended in the media frenzy, all the forecasts that accompanied the spectacular international emergence of José Cura have materialized into a career beyond measure. In the following interview, the tenor refers to various interpretive aspects of Samson's role.

CS: - How is the voice classified for Samson, in reference to the traditional classifications?

JC: - If one wanted to interpret Samson in the spirit of what is strictly understood historically as the stylization of French music, we would have to start with a voice that isn't so much light as a voice with much less attack. It would require very different to approach singing the role as it was conceived in 1890. If we want, instead, to interpret a contemporary Samson, in light of the acoustic challenges we now face, the difference in vocal concept is enormous. Rather than assigning the role to a classification based on the number of decibels produced, I prefer to think of it based on psychological color, which is a determining factor in the character's profile.

CS: - What are those acoustic challenges?JC: - First, the size of the theaters, which are enormous today. Then, there is the fact that the orchestras sound very heavy because of the harmonic density of modern instruments. A third, more dramatic point is the rise in pitch. Most of the operas that we interpret today were written between 1800 and 1900. At that time, the pitch oscillated between 432 and 435 cycles, which means that compared to the pitch we use today, which is almost 445 and even 450 cycles, we have a rise of a third of a tone and even a half tone. In short, this has caused a significant change in the way we sing compared to the past. The logic of these conditions means that the vocal quality of certain dramatic characters is assigned to much more robust and harsh voices. CS: - Regarding the tessitura in which Samson is written, for a dark, baritone tenor who sings almost the entire opera in the mid-low register. How do you resolve the arrival of the high note above the orchestra and chorus? JC: - With a high note that's very thick, broad, and grand. We're talking about a mythological hero whose entire legend is based on physical power, so it would be ridiculous for the character to sing those notes with the same acoustic presence as, for example, a high note from the tenor in La bohème. No matter how beautiful and accurate the sound, it would lack dramatic intensity. That's the great vocal challenge of Samson, and of dramatic tenor roles in general.

CS: - What is your perception of the character in relation to vocal brilliance?

JC: - Samson has very defined moments in which he can shine for different reasons. In the first act, he is an aggressive character, an Old Testament warrior. In the second act, his aggression transforms into sensuality and extreme insecurity in his relationship with himself, with God, and with the feminine. In the third act, which is spiritually the most interesting, Samson redefines himself. Throughout the first part of that act, Samson should sing in a half-voice. In the second, however, we have another kind of singing. It is the instance of redemption understood within the framework of a culture located 1,500 years before Christ. The possibilities for performance are broad and diverse.

CS: - Does this role give you satisfaction?JC: - Very much! Samson is one of the roles to which I owe the most success on stage. It is one of the characters that has given me the greatest satisfaction throughout my career. José Cura: "They sold me as a sex symbol tenor, but I survived" Ambitoweb Marcelo Zapata 3 July 2007

[Computer-assisted translation // Excepts]

There's only one thing clouding Samson's good mood this morning: he woke up with the onset of a cold, something that for a world-famous tenor (for any singer, really), is terrifying. "We'll get it under control," he tries to smile.

José Cura, the internationally renowned Rosario native, has been easing into the lineage previously occupied by Domingo, Carreras, and Pavarotti for the last decade and half. After an eight-year absence from Argentina, Cura is performing in one of his favorite operas, Camille Saint-Saëns' Samson et Dalila during the current Colón season, though the performance relocated to the Coliseo [due to the Colón’s on-going refurbishment], a theater to which he rightly attributed his morning malaise. "It's cold on stage, too cold, and I think I caught a cold there. The chorus can at least wrap themselves up in their heavy costumes, but I have to go out in my thin shirt."

A resident of Madrid for several years ("I think Spain is the European country with the best quality of life, the best food, and the best climate. I couldn't stand, for example, living in a cold country"), Cura already displays a slight Hispanic accent in his slow manner of speaking. From the 16th floor of the Panamericano Hotel, where he is a guest during his stay in Buenos Aires, we can see both the Obelisk and the Teatro Colón. At the beginning of our conversation with this newspaper, he recalls his visit in 1999, when he sang the lead in an Otello that divided the critics. He also appreciates the fact that Ambito Financiero was the first national newspaper to publish an extensive article about him in 1993, when few people knew him.

"The review that Abel López Iturbe published in Ambito about my Otello was the only intelligent one. The other critics were expecting me to “scream” the role and they were disappointed. But López Iturbe was the only critic who heard something different and he wrote about it very well. Eight years have passed since then, and eight years in the life of an artist like me, who does a hundred performances a year—that is, eight hundred performances from that Otello to today—is a long time. My Otello is no longer the same; of course. Today I sing it with more authority. There's a huge difference between that young man and the mature artist of today. That's why, looking back, I would divide those 1999 reviews into the aggressive, the dubious, and the observant, and Ambito's falls into the latter category.”

Journalist: Would you do Otello here again?

José Cura: No, not at the Colón. You never bring the same role to the same theater. Fortunately, the reviews for this Samson and Dalila were unanimously positive, because I think my performance gave them the reason for it to be so. The future could be glimpsed in 1999. Now it’s evident.

Q: Do you listen to your records from back then?

J.C.: Never. I think the artist who listens to his records is like those idiots who spend all day looking at themselves in the mirror. Besides, I'm very critical. If I spent all day looking at myself in the mirror, I'd see myself become uglier and uglier.

Q: How do you choose your roles now?

J.C.: I choose those with which I know I won't get bogged down. The "all-terrain" singer doesn't exist, just as there is no such thing as an all-terrain car, because if they drove one that claims to be around a city they would crash everywhere. And that choice is only possible with experience and self-knowledge, understanding of the international circuit, and so on. There's no choice directly linked to a taste for a given role but rather to the possibility of being able to say something new with it. The only other thing that matters is that they also have dramatic interest. Otherwise, I'm not interested.

Q.: No requirement for vocal showmanship...

J.C.: None of that. I have never been interested in going on stage to sing beautiful notes, not before and not now, despite having acquired technical mastery. Beauty for beauty's sake bores me.

Q: But doesn’t the 21st-century public also demands that?

J.C.: Not always. Beauty for beauty's sake is always attractive, although I'm sure it ends up boring. And that applies to all areas. A very beautiful man or woman standing in a shop window loses interest the second time you pass by. Beauty is one-dimensional. Like ugliness. Today, for example, there's a lot of insistence that there are no new voices but that's not true. What is true is charismatic personalities are not appearing. I believe the infamous globalization, far from uniting borders, dissolves and crushes personalities. Everything tends to unify, to assimilate, to be the same. Merchandise is moving in the same direction, album covers look alike, even music is starting to sound the same.

Q: But today we have many technical resources that weren't available before.

J.C.: It's true, we've grown enormously in technical capacity. The means available today, in every sense, are amazing, but they seem to have developed at the expense of personality, of the ability to transmit through charisma. In the past you would go to buy a record and the salesperson would advise you, take the time to discuss the music. Today, CDs and DVDs are displayed on shelves, just like sausages. Record labels pay large malls and retail chains to have their products occupy a certain place of privilege on the shelf. That's not illegal, of course; you buy a place like you buy a record. But that, for example, inhibits the ability of the old-fashioned music seller, who displayed the recordings he thought were the best.

Q: You also go through the marketplace…

J.C.: Of course, but both I and the few other artists of my generation who are still around, are already beyond good and bad. We have survived all of that. We are who we are. We have full schedules. Unfortunately, those who come after us aren't doing as well. There are so few who make it through the line of fire. They're thrown straight into the supermarket, they sell one or two of packages of sausage but if they don’t sell the third, they're dumped.

Q: How was it in your case?

J.C.: I was a pioneer in this. When I began my international career, the marketing that was applied to me was one of the first major marketing campaigns that used not only my voice but also my appearance. There was talk of me as an opera "sex symbol" and nonsense like that that distracted people.

Q: But it didn't harm you.

J.C.: No, but it caused a lot of confusion ant that bothered me. There was even talk of a "new talent" who emerged "overnight," even though I first went on stage at the age of 12. But, of course, they tried to sell me as if I had won on "Operación Triunfo" or "Cantando por un sueño." Luckily, my background and my previous training allowed me to withstand that enormous pressure and now, free from all this, I continue managing my career well while trying to pull some of the younger singers along. Unfortunately, the rope sometimes breaks when pulled on, because the new singers are under much greater pressure than we were and have less technical preparation.

Q: Do the newcomers want to be instant stars?

J.C.: No, it’s not them. When you talk to them, you realize they're very aware of the work they have ahead of them and the difficulties they must overcome. The problem is the commercial system that wants to throw them out right away to find a new vein of income, and without providing the necessary technical preparation.

Q: How did you find your colleagues at the Colón?

J.C.: I'd say they were good, although I wasn't there long enough to fully evaluate them. Here, as an old singing teacher used to say, they sweat a lot. That doesn't mean those of us who left don't work sweat as well but of course, the results we get aren't the same.

What I have noticed is that there's a degree of optimism with the new management at the theater I never felt before. They know they have to fight but that also know that something can be achieved through fighting. On the other hand, when I came in 1999, it was all about the fight, not the results. Now, the singers and the orchestra members are aware that everything is difficult and their attitude is different. I've never kept quiet about anything, which is why I say that the current management of the Colón is the most positive in the last 25 or 30 years. I don't want to get into politics; I'm speaking only as an observer who has known the Colón Theater intimately since 1983, and it seems to me that if the new head of government makes changes and starts all over again from scratch, the future will become very uncertain.

Q: You've already said you won't be coming for the Centennial.

J.C.: Unfortunately, it's impossible. As soon as Marcelo Lombardero took over as artistic director, the first thing he did was contact me to offer me the role of Radamés in Aida for the reopening performance. But I have a contract that ends three days before that date, and another that starts four days after. If Argentina were, say, a two-hour flight away, I would gladly make the effort and sing at least the opening performance.

|

|

.jpg) |

|

.jpg) |

Also from this this period

2008 - 2009 Shared production

|

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “The merit of the final scene goes to José Cura, who seems reborn and purposefully refining the interpretation of the role that fits him so perfectly.” La Repubblica, 2 June 2008

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “José Cura as Samson also does well. If recently he seemed to be chasing after the good old days when his voice was a flood, he now uses with good “economy,” even stylistically, the means at his disposal. Applause.” Corriere della Sera, 15 June 2008

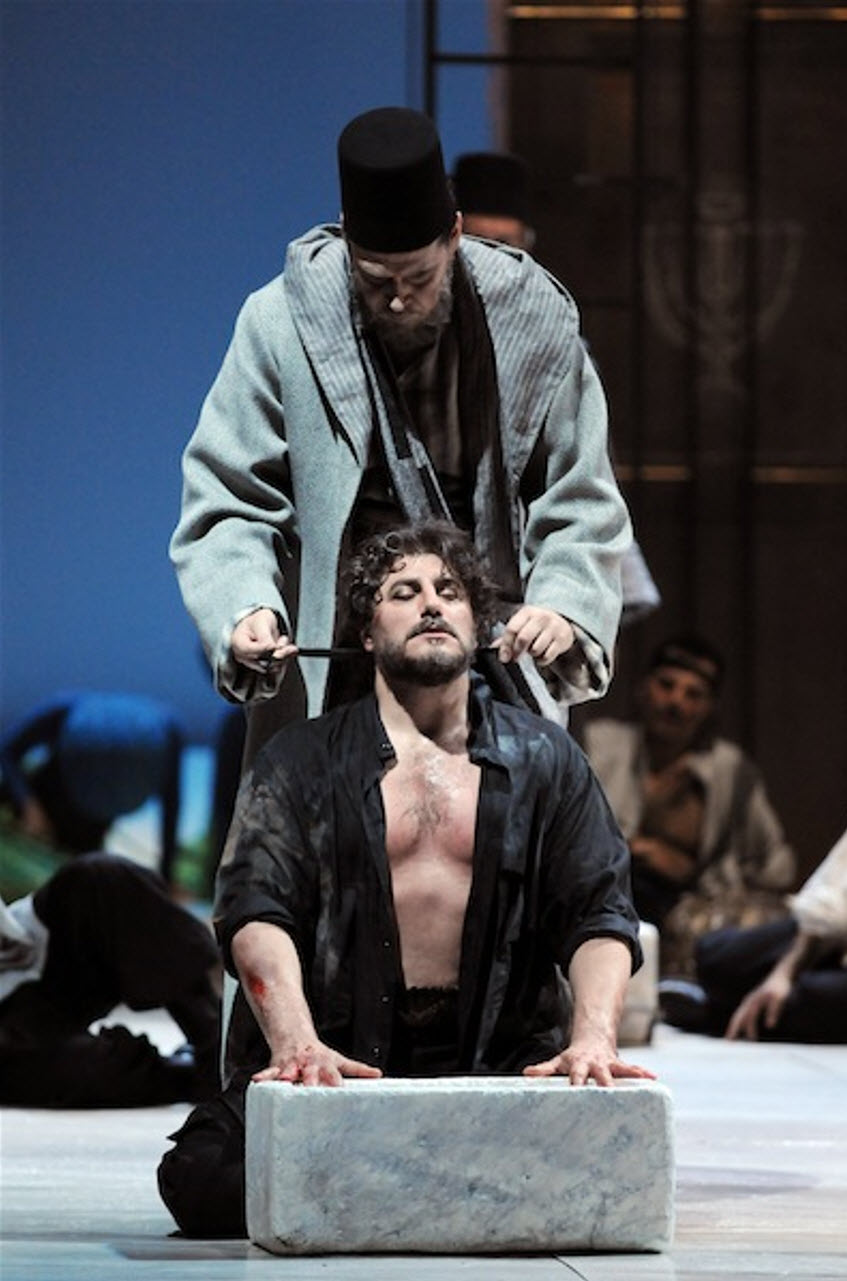

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “Dalila, the beautiful Philistine who betrays Samson for racial hatred and thirst for revenge is Russian mezzo Julia Gertseva. She is beautiful, with a sumptuous voice, sings well, and is both musical and a musician. However, that necessary spark of inexpressible femininity fails to materialize. No such problem with the performance of José Cura. In the first act, shirt opened across his buff chest, he runs agilely up and down the metallic stairs that divides the two levels of the set, with the oppressive Philistines occupying the upper level, the oppressed Jews on the lower one. And if the instrument is not be what it once was, any ungenerous thought is swept away in the second act, that of seduction and betrayal, where the emphasis is more intimate and conflicted to prepare for the arrival of the true emotions that comes in the third act, where shorn, wounded, and suffering, [Cura] shows himself to be a mature and sensitive interpreter, with the true timbre of an artist. A great success…” Il Sole 24 Ore, 5 June 2008

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “The Bologna season ended with a resounding success for Samson et Dalila, marked by the rhythmic ‘ola’ of the final applause. Principle merit must be attributed to that vocal and interpretive hurricane who answers to the name of José Cura. One of the roles felt most keenly by the Argentinean tenor from Rosario is Samson. You may have seen and heard him in action at the Teatro Regio in Turin when he caused a sensation by appearing in loin-cloth, or at the Liceu in Barcelona when his unexpected performance substituting for José Carreras resulted in him becoming a favorite of that theater. In short, Cura is the only Samson. Beyond the undeniable stage presence, it must be noted in this role [Cura’s] obvious musical engagement in respect to the score and in adherence to the signs of expression, arriving at a display of unthinkable and sweet mezzevoci in the vocal surrender, where the timbre of precious bronzed amber stands out in all it manly beauty. Thus applied we want to see and listen more often but one thing more is also Cura: unpredictable. However, when he is on stage he is the catalyst who demands the attention while the other struggle twice as hard to be noticed.” L'Opera, August 2008

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “The predominant tessitura of Samson is congenial to both the beautiful voice of José Cura and his temperament. The broad timbre, encased in burnished velvet, is at its best in the middle tones…in the third act the singer offers the best of himself and the results are excellent, showcasing a man defeated but not tamed, making credible and touching the prolonged moral agony. This Samson, in fact, is not drawn from the religious, maintains at all time a very strong human nature with no hidden ‘divine mission,’ combining fragility and vulnerability to make the events even more tragic.” Teatro.Org, 6 June 2008

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “With his natural fighter’s temperament, José Cura mesmerized the audience and it would be difficult nowadays to find a more convincing Samson with the requisite quasi-baritonal qualities.” Opera Now, September/October 2008

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “With great pleasure we found José Cura in wonderful form, extraordinary in stage craft and incisive in accents and phrasing. A triumph.” GBOpera Magazine, 11 June 2008

Samson et Dalila, Santander, August 2008: “Tenor José Cura undoubtedly has style, and his beautiful timbre shone brightly in his debut in the Santander Festival. He has the force and dramatic quality necessary [for this role] and was splendid in the second act aria, Mon coeur s'ouvre á ta voix, sung with Dalila.” El Diario Montanes, 29 August 2008

Samson et Dalila, Santander, August 2008: “There is no doubt that anticipation had been raised about José Cura's portrayal of Samson. The Argentine's stage presence is both very powerful and magnetic, perhaps somewhat exaggerated, even overwhelming. In that sense, he creates a believable character, albeit with certain aspects of posturing, designed to delight the audience visually but at the same time interfering with the perception of his vocal qualities, which proved uneven throughout the evening, particularly in the first act. The second act brought us the most inspired Cura of the evening; the Argentine seemed to calm his fiery locomotor, to the benefit of his art: it can be said that he shone in what is undoubtedly the opera's star aria, Mon coeur s'ouvre à ta voix. The third act again showed some difficulties, though fortunately not at the precarious level of the first act. The singer's French, at times unintelligible, deserves special mention…In short, an uneven operatic evening that nonetheless drew enthusiastic applause from an audience.” El Diario Montanes, 30 August 2008

Samson et Dalila, Santander, August 2008: “The vocal attraction of the evening centered on tenor José Cura, who is a true diva and presented as such. Cura has great confidence, a powerful voice, and very good delivery. He performed at a great level and received the evening's greatest ovations. The Santander performance was a notable success and the audience, which packed the venue, celebrated the triumph.” El Mundo, 29 August 2008

Samson et Dalila, Santander, August 2008: “In the cast, José Cura reigned supreme, as expected in one of his favorite roles. It's clear that the tenor lacks refined vocals but the forcefulness of his singing overcomes the lack of care in his diction, overwhelming with richness and demonstrating a power as Samson that captivated the audience.” ABC, 31 August 2008

Samson et Dalila, Liege, September 2009: “Strictly balanced between the hieratic general and the psychological particular, he directed all the actors except the Argentine tenor José Cura who was allowed free rein and for good reason: the singer knows the role thoroughly, he brings to it his deep, warm timbre (habits, too) and, despite some reservations in style and diction, he embodies, by his immense talent, his charisma, and his generosity, the trump card of the production. The Russian mezzo Julia Gertseva (Dalila) has a superb voice but she needs to move out of her reserve, in sexiness and cruelty, to match the fiery temperament of Cura.” La Libre, 21 September 2009

Samson et Dalila, Liege, September 2009: “This premiere of the 2009/10 season was not really a success. Due to the renovation works at the Théâtre Royal on the Place Grétry, the opera was performed in the Country Hall Ethias. It is a hall intended for sports events: completely devoid of atmosphere, with terribly bad acoustics, uncomfortable chairs and so spacious that the action on the improvised stage could barely be followed. Pity, because this only partially did justice to José Cura's performance. You could, of course, hear that his voice is ideal for this role, although his French diction was nothing to write home about. But he has the right voice type, unforced high notes and he knows how to give the role the right amount of drama. Moreover, he has the physique for Samson: when he strode onto the stage in the first act with his chest bare and a donkey's jawbone in his hand, we immediately thought of Victor Mature in the 1949 film by Cecil B. DeMille. But the beautiful performances were severely hampered by the poor acoustics.” Opera Gazet, 20 September 2009

Samson et Dalila, Liege, September 2009: “Julia Gertseva, with a beautiful figure and a large mezzo voice, displayed nothing of the irresistible seducer. And she needed the sensuality to cope with José Cura’s Samson: powerful, carnal, of real presence. If in his first ‘speech’ exhorting the Hebrew to free themselves from their chains the tenor mishandle the accuracy and the line of singing, in the second act as a man torn between his God and Dalila he revealed mastery of his broad, solid tonal range, from the low register to the high. Cura unleashed in the third act, painfully, tragically.” Le Soir, 21 September 2009

|

|

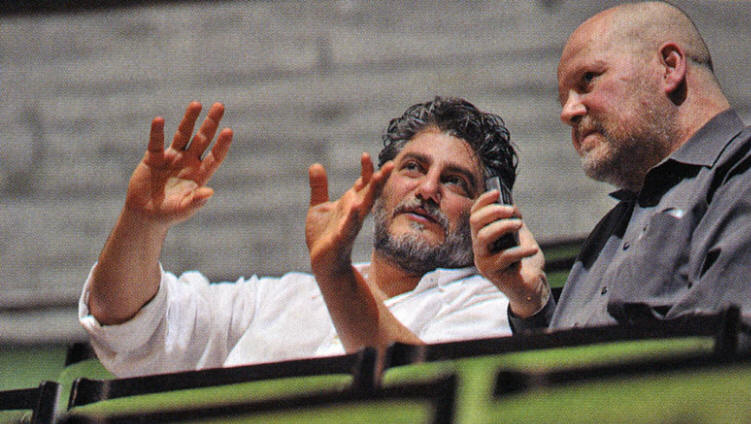

Samson et Dalila – Teatro Comunale

La Republica Bologna Francesca Parisini Francesca Parisini 28 May 2008

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpts]

Cura: “When someone kills, claiming to kill in the name God, that person is a murderer and a terrorist.”

“Samson et Dalila is a story from 3500 years ago but it has never changed. When someone kills or kills himself claiming to kill in the name God, that person is a murderer and a terrorist.” So says José Cura, the Samson in the new staging of the Camille Saint-Saëns’ opera in three acts at the Comunale. “Samson and Otello by Verdi are the roles with which I grew up artistically,” says the great Argentinean tenor, who for the last twelve years has been the Samson interpreter of excellence: he has done a dozen different productions, as well as various recordings. Starring with him as Dalila is Julia Gertseva; the director is Michal Znaniecki from Poland. The production is a co-production of Comunale di Bologna, where the work debuts, and Opera «Quella di Samson e Dalila è una storia di tremilacinquecento anni fa, che però non è mai cambiata.Royale de Wallonie, Opera Wroclawska and the Foundation Teatro Lirico Giuseppe Verdi in Trieste. «Queste produzioni così numerose - spiega il sovrintendente del Comunale Marco Tutino - sono l´unico modo per uscire dalle difficoltà in cui versano oggi i teatri». "There are so many productions,” explains the Superintendent of the theater, Marco Tutino, “because it is the only way to survive the difficulties today theatres today.”

Although it is a masterpiece of the classical repertoire, Samson et Dalila has been missing from Bologna for 57 years. To conduct is an old acqaintance of the theater, Eliahu Inbal, currently musical director of the Fenice in Venice and chief conductor of the Orchestra Metropolitan of Tokyo. “I directed my first opera,” the maestro says, “Electra by Strauss, in 1969. But my first time here was in ’63, for some symphony concerts, when the orchestra was housed separately for six years. …”

“This opera is timeless—I concentrated on its universal meaning,” says the director Znaniecki, who attended the University in Bologna. “I thought of staging the conflict between two cultures, between two different groups. The first, whether they are Palestinians or Hebrews, are more connected to the land. The second flaunts the security of being the more advanced, the higher culture. Even the costumes, designed by Isabella Comte, stress the diversity between the two groups: the first are simple and the second is more sumptuous, almost exaggerated. To enrich the scene, there are images that relate to events like 11 September or l’Intifade Palestinian, with children who throw stones on the Israeli soldiers. But that is not part of it,” assures the director.

“It’s a complex work which was born as an oratory,” continues Cura. “It is also very strong and highly controversial, considering that the similarity with the reality of today’s events is not purely coincidental." José Cura is now a frequent visitor to the Bologna theater ("it is the only one in Italy where I work," he claims, letting a polemical note slip out); in fact, Superintendent Tutino has announced that Cura will open the next opera season as the lead in the rarely performed opera of Nero by Boito.

"This is a complex work, which was born as an oratory - continues Cura -. Furthermore, it is a very strong and highly polemical work, given that any similarity with the facts of today's reality is not purely coincidental." José Cura also has a consolidated relationship with the Bologna theatre ("it is the only one in Italy where I work", he claims, letting a polemical note slip out). So much so that the superintendent Tutino has announced that he will be the protagonist of the opening of the next opera season, entrusted to a rare opera such as Boito's "Nerone".

|

|

|

|

The Opera World Rewards Strong Performers EFE [Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpts] Santander, Spain - The Argentine tenor José Cura says the world of opera requires "a very strong back" and that only the strongest performers last, a "natural law" that extends to other areas such as sports or politics. In an interview in the Spanish city of Santander, the singer, composer, conductor and director said that after 20 years on stage he has seen many singers broken, talented or not. Cura noted that only now can he afford to seek new paths but believes that he still needs to break stereotypes and end, for example, with the idea that an interpreter cannot also be the director of an opera in which he performs. "A [Robert] Redford or [Robert] De Niro can direct and act and nothing happens. With a good team of assistants and good coordination, anything can be done ," he said. Following his debut at the Santander International Festival, the multifaceted musician awaits a new project for Samson and Dalilah in 2010, in which he will sing, direct and design the scenery. Furthermore, Cura will return to his native Argentina, though it will not permanent, at least for now, because of his children. "Their lives are here, their friends, their roots. It would be like breaking the family," he explains. However, if in ten years or so he gets a flattering offer from his country he can live between Spain and Argentina, "where there is not only the Colón but other great theaters. Cura was trained as a composer and conductor in Argentina but life circumstances led him from a country emerging from dictatorship to a Europe in need of new voices. "The first five or six years are very hard because they throw everything at you: the media, the public, agents, theaters ... and if your back is not strong, they'll crush you," he explains. "Those of us who made it through that filter, we live to tell about it and are able to enjoy the maturity of our career." The Argentine musician argues that it is the obligation of the interpreter is to analyze the society in which they live and bring that aspect to their characters if opera is not to become "a museum piece.” That’s why he has shown another side of Otello since 2001. Cura has little time for composing but he felt the need to put music to seven sonnets by Neruda, his last work. And while continuing to record, he understands that the market is in a complete redesign, because if in 1997 the finish line in classical music was to sell 200 thousand copies, today ten thousand ears a gold record. For the Argentine tenor new technologies are rewarding to "the career artists in claiming his profession: to communicate directly with the public.

|

|

Tenor José Cura returns to Spain as Samson

Cura has achieved worldwide recognition on various stages around the world with the role

EFE El Universal 26 august 2008

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

Argentine tenor José Cura returns to the role of Samson, one of his most acclaimed characters, in a new version of Camille Saint-Saëns’classic, with which he debuts tomorrow at the International Festival of the Spanish city of Santander (FIS).

For the artist, the biblical story of Samson and Delilah, one of the great works of the international opera repertoire, demonstrates that in more than three thousand years "nothing has changed" and that killing in the name of God, "whether his name is Yahweh, Krishna, or Allah, is cowardly."

"In my opinion, regardless of religion, regardless of political affiliation, when you kill, you kill, and if it's done in the name of God, then so much the worse," the tenor said at a press conference today.

José Cura will once again play Samson in this production by the Teatro Comunale in Bologna and is being presented for the first time in Spain. Mezzo-soprano Julia Gertseva, in the role of Dalila, and baritone Mark Rucker, as the High Priest, will share a stage conceived as an abstract space. For this production, according to Polish director Michal Znaniecki, two different worlds have been created, one full of color and the other in black and white to recreate a biblical conflict between Jews and Philistines, which could also be a conflict today.

The director confessed that José Cura helped him better understand this opera and has led him to abandon, for example, the classical approach to ballet, which is a common feature in all French operas, in order to give it greater emotion.

Eliahu Inbal also praised the tenor's "great musical personality," joking that in Spain Cura only sings on the coast: at the Liceu in Barcelona or now in Santander.

"Let's see if I'm invited to a theater a little further inland," laughed the Argentine singer, who hasn't returned to Madrid's Teatro Real in eight years when he challenged a section of the audience that had booed him after the famous aria Di Quella Pira from Il trovatore.

Among his plans is to return to another of his facets as a musician, that of orchestra conductor.

He made his debut a decade ago in front of the orchestra of the Bologna Theater, where, as he revealed in Santander, he will return next January to conduct “a whole symphonic concert, with music from the American continent from North to South, from Barber to Piazzola.”

“Ten years later I will meet again with the same orchestra, all older, balder and more gray-haired, but perhaps a little wiser. I think it will be a very fun concert,” he predicted.

And when asked if at some point he will consider giving up singing to devote himself to conducting, he resorts to a phrase his wife repeats often: “Tells me I can retire when I have paid off the mortgage.”

|

|

"The stage is the best psychotherapy for an artist." El Diario Montanes Maxi de la peña 29 August 2008

[Computer-assisted Translation / Excerpt]

José Cura believes there are more divas in politics than in music and believes bad taste is the imitation of old molds.

Q: - Are critics ultimately conservative? Do they simply wants "jack, queen, and king" and penalize passion? JC: - When I was younger, I was a bit of a "blind bull" and gored people left and right. With time, I matured and learned when to gore and when not to. I think critics, just like the audience, have different tastes and like different things. What I will say about critics and audiences is that regardless of whether you like the old style better—or to put it more brutally, you think nobody sings as the dead sang, which is fine because it is a form of respect for the past—they shouldn’t deny the merits of the present generation. I’m not talking about me personally but about everyone. Young people need encouragement to get on stage, and if the people who are watching and making comments are always focused on the past, there can be no evolution, no change, no progress. Q: - Are there many Taliban among the opera audience, a few hardened tribes? JC: - There's a lot of Tthat when you're in a group, because it's easier. On your own, you may think differently but you get carried away a bit by the mass. I'll make the same request for the members of the audience as for critics: respect and admiration for the past, encouragement for the present, and even more encouragement for the future, for our children, who will manage everything that's to come. Q: - You're a temperamental person. Do you suffer a lot when things don't go well for you? JC: - I suffer quite a bit in general. On an artistic level, on an administrative level, on a human level, when I see that things could be a certain way and aren't, I think I can get upset like any other human being. Especially when I see that the evidence is one way and the reality is another. Q: - What is a stage for you? JC: - The stage, for an artist, for an actor or a singer, is that place of illusion. It's the place where you can be a cowboy, a king, a villain, or a hero, and it's where you can unleash our healthy schizophrenia. It's the best psychotherapy. Q: - Are you a self-taught singer? JC: - Just because I have a personal way of producing my sounds doesn't mean that my way of singing isn't studied and thoughtful. After thirty years on stage and twenty years of an international career, I couldn't continue singing with a fresh and healthy voice if I didn't have the necessary studies and learning. Now, I'm self-taught because it's the way to have a personality, a way of expressing myself. I've had very good teachers but in the last fifteen years, I've preferred to be the lord and master of my responsibilities, my flaws and virtues of what I do so that when the audience hears me, they say, 'This is the Cura sound,' whether they like it or not. When you see these kinds of assessments, they always correspond to an artist who has been somewhat rebellious.

|

|

Samsón and Dalila shows the cowardice to kill in the name of God Saint Saëns’ opera stars the charismatic Argentine tenor José Cura

Eldariomontenas Maxi De La Peña 27 August 2008

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpts]

“To kill in the name of God is the way of cowards.” The charismatic Argentine tenor José Cura, the male lead in the opera Samson et Dalila by Camille Saint-Saëns, wants to accent the ‘sad’ force of the argument found in this work inspired by the Book of Judges from the Old Testament. The Argentine singer and conductor attended an introduction yesterday of the opera being presented during this year’s International Festival of Santander, a production made possible by the joint efforts of four European theaters: Comunale de Bolonia, the Ópera Real de Wallonie, the Ópera de Wroclaw and the Giusseppe Verdi de Trieste.

[…]

For [conductor Eliahu] Inbal, it is a question of the opera being of the ‘highest quality’ and of emphasizing something that is centered on the charismatic figure of José Cura “that supports the musical tension.” He thanks the director, Michal Znaniecki from Poland, for his great contribution since “he has found the visceral sense of the opera.”

José Cura, who along with many others planned to stroll Santander next to his wife and son and to visit Santalilana del Mar, mused aloud about the reasons “operas are so often presented in the least attractive cities. Here, two things are joined. If things go well, I hope to return.”

On a professional level, he explained that there are many ties that bind him the Bologna theater. “The reunion with Michal Znaniecki, who has for the last three or four years been the artistic director of Opera Warsaw and with whom I worked in the Comunale, has been special. These are the returns of classical music.” The tenor jokingly complained about singing in the coastal cities of the Iberian Peninsula (Barcelona, Valencia, Lisbon, and now Santander), to which he added: “I hope they invite me to sing more often on the inside.”

The Argentine opera star didn’t waste [the opportunity] presented by this new adaptation of the Camille Saint-Saëns to analyze the plot background. The action is developed in Israel, during the occupation of the Philistines, in the time of the Judges. “In my opinion, when it is by religion, as represented in the current political climate, that one commits suicide, when one kills himself in the name of God it is much worse. It has been 3,500 years since the war between the Philistines and the Jews and nothing has changed in the world. As human beings we are responsible for our actions and should not seek out excuses from a superior being.”

On the hypothetical question about his future retirement, Cura threw up his hands with both a sense of humor and of reality: most opera singers are not millionaires, except those who belong to the ‘star system.’ “My wife,” he added, “tells me I can retire when I have paid off the mortgage.”

|

|

"Killing in the name of God is cowardly, whether His name is Yahweh, Krishna, or Allah." EFE 26 August 2008 [Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt] Argentine tenor José Cura makes his debut at the FIS with a new production of Samson et Dalila, which will be performed Wednesday and Friday and shows that in more than three thousand years "nothing has changed" in the world. Argentine tenor José Cura will make his debut tomorrow at the Santander International Festival (FIS) with a new production of Samson et Dalila by Camille Saint-Saëns, an opera that, in his opinion, speaks of the fact that killing in the name of God, "whether His name is Yahweh, Krishna, or Allah, is cowardly," and shows that in more than three thousand years "nothing has changed." "In my opinion, regardless of religion, regardless of political affiliation, when someone kills, they kill, and if it's done in the name of God, so much the worse," he said at a press conference today. The biblical story, which the composer of The Carnival of the Animals turned into one of the great works of the repertoire, conveys, in his opinion, that same idea, as well as that human beings should "take charge of their own affairs and not seek in a higher being, or whatever you want to call it, the courage we don't have." José Cura, one of the most popular voices in opera, will once again embody a character for which he has been acclaimed in theaters around the world in this production by the Teatro Comunale in Bologna, which premiered on May 31 in the Italian city and will be performed tomorrow for the first time in Spain. This new version of Saint-Saëns's opera, which is not a very common title in the programming of Spanish theaters, is musically directed by Israeli maestro Elihau Inbal, who will be in the pit opposite the Orchestra and Chorus of the Teatro Comunale of Bologna, while Polish director Michal Znaniecki is in charge of stage direction. Mezzo-soprano Julia Gertseva, in the role of Dalila, and baritone Mark Rucker, as the High Priest, will share with the Argentine tenor a stage conceived as an abstract space. As Znaniecki explained, two different worlds have been created, one full of color and the other in black and white to recreate a biblical conflict, pitting Jews against Philistines, but which could also be a modern-day conflict—although, in his opinion, that is something for the audience to understand and decide. The director confessed that Cura helped him better understand this opera and has led him, for example, to abandon the classical approach to ballet, which is a staple in all French operas, in order to give it more emotion. Elihau Inbal also praised the tenor's "great musical personality," joking that in Spain he only sings on the coast: at the Liceu in Barcelona or now in Santander. "Let's see if I'm invited to a theater a little further inland," added the Argentine singer, who hasn't returned to Madrid's Teatro Real since he challenged a section of the audience that booed him after the famous Di quella pira from Il trovatore. Among his plans is to return to another of his musical roles: that of orchestra conductor. He made his debut a decade ago with the Teatro di Bologna orchestra, where, as he revealed in Santander, he will return next January to conduct "a full symphonic concert, with music from the American continent from North to South, from Barber to Piazzolla." "Ten years later, I'll find myself with the same orchestra again, all older, balder, and grayer, but perhaps a little wiser. I think it will be a very fun concert," he predicted. And when asked if he will ever consider giving up singing to dedicate himself to conducting, he resorts to a phrase his wife has often repeated: "You can retire as soon as you pay off the mortgatee."

|

|

José Cura says that only the Strongest Artists Endure in Opera

EFE 30 August 2008

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpts]

A composer, orchestral and stage director as well as a singer, he can now afford to explore new paths, although he believes there are still clichés to be broken such as the idea that a performer cannot also be the director of the opera in which he performs.

"A Redford or a De Niro directs and acts, and nothing happens. With a good team of assistants and good coordination, anything can be done," said this versatile musician in an interview with EFE. He recently debuted at the Santander International Festival and has projects awaiting him, such as a new Samson et Dalila in 2010, in which he will sing, direct, and create the scenery.

Also on his agenda is a Verdi’s Requiem, which he will conduct in his home country. The possibility of returning to his homeland is a recurring topic of conversation between the tenor and his wife, but for the moment, they don't see it as being fair for their children. "Their whole life is here, their friends, their roots. It would be like breaking up the family," he explains.

However, he doesn't rule out the possibility that if he receives "a flattering offer" from his country in ten years, he could live between Spain and Argentina, "where not only is there the Colón Theater, but also magnificent theaters in the interior."

Where he might return, although it will have to wait until 2012, is to the Teatro Real, where he hasn't performed since he challenged a section of the audience that booed him eight years ago. He asserts that relations with the Madrid theater are "really good."

José Cura trained as a composer and conductor, but his life circumstances took him from an Argentina emerging from dictatorship to a Europe in need of new voices.

And the path he chose is demanding for those just starting out. "The first five or six years are very tough because everyone is on your back: the media, the public, the agents, the theaters... and if you don't have a strong back, they crush you. Those of us who have managed to pass through that filter live to tell the tale and can enjoy the maturity of our careers," he explains.

"You have to get through the era of big magazine covers, the opera sex symbol, and the hope for the future, all that nonsense that's part of show business, and if you can handle it all with your head on straight, then you can publicly declare yourself a mature artist, one who has survived and is ready to transmit an art form with a certain authority," he adds.

Two great characters stand out in his repertoire, Samson and Othello, who are "sadly tied to the present day" and who he can't build on his experiences as Stanislasky commands because "luckily" he is "neither a murderous fanatic nor a mercenary traitor to his race."

His Otello "has a different face" since 2001, and he argues that the performer's obligation is to analyze the society in which they live and apply it to their characters if they don't want the opera to become "a museum piece."

José Cura has little time to compose, but he has found the time needed to set seven of Neruda's sonnets to music, his latest work. And although he continues to record, he understands that the market "is undergoing a complete rethink." If in 1997 the goal in classical music was to sell 200,000 copies, today 10,000 copies earn a gold record.

|

|

|

The chance for SamsonLa Libra Nicolas Blanmont 18 September 2009

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

Samson et Dalila opens the season outside the walls of the ORW. Stafano Mazzoni definitely has connections. To sing the role of Samson in Liège, he has called upon one of the most well-known interpreters of the role on the international stage: José Cura. For the biblical hero with the precious hair, the Argentine tenor (who, not to waste his time, is also a conductor, composer, and director) has charisma and power – as much physical as vocal. Besides, he has performed it almost every year since assuming the role at Covent Garden (1996) through Bologna last year, which is also the production that will be staged—with necessary renovations—in Country Hall Ethias, on the Sart-Tilman heights. Samson pleases me from the vocal point of view and in the physical sense: even if his power comes from God and not from muscles, the fact that I am a rather tall and strapping man corresponds well with the image the audience has of this character. But I do not like what he is, even if he is a character in the Bible – but then not all the characters in the Bible are saints! This guy is rather negative, a revolutionary in the beginning, which is pretty nice, but what he does in the name of God, which unfortunately is very modern, is less nice. It is a story we see written daily in the newspapers and I do not think only of Allah, or even religions, but also anything which imposes ideas by force, whether in the name of money, oil, or whatever else. Unlike the recent production of the Flemish Opera, directly transposing the action to the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the production in Liège is located in a less-dateable world: no updating, but costumes blending oriental and science fiction, with some current references (the Intifada) but also some mythic images (the broken columns and the crumbling temple in the end). Cura has no shortage of ideas on the matter, since he will be staging the work (while singing it, too) in Karlsruhe next year. One might be surprised to see Cura, a tenor at the top of he art, to diversify between conducting and directing (and he happened to do both on night, like Cavalleria rusticana in the pit and Pagliacci on stage) when at 47 years of age he is not yet force to think about his retraining. Instability? By no means. ‘The routine is reassuring, and I could be satisfied just singing three or four roles for the next twenty years. But I do not like to sleep and I do like risk: so, when someone suggested directing or stage designing, why not? These are trades I know – I studied conducting before I started singing – and where, without claiming to be the best, I am not doing too badly. There are better, but there are worse. I usurp nothing – no one asks me to build a hospital or pilot a plane! – and I do not do it for money because the fees for these are about a quarter of the fees are about a quarter of my tenor fees.

|

|

José Cura, Hero and Rebel Le Soir Michele Friche Wednesday, September 16, 2009

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpts]

L'opéra de Wallonie launches its new season outside it walls: a rare opera, Samson et Dalila by Camille Saint-Saëns and for the first time in Belgium, a renown tenor who has things to say. With his strong stature, his Samson could break the columns of the temple of the Philistines with a flick! Conductor, composer, director, singer, teacher, photographer, father, José Cura is a warm-hearted artist who speaks his mind. He begins by setting the record straight: ‘My academic background is that of a conductor and composer. But with the crisis is Argentina, the difficulty of starting off in this business, I needed to leave to eat. One of my teachers at the university advised me to learn to sing. I did not want to: the singers, they are all hysterical, I thought . . . But I had a voice, generous.’ José Cura switched careers, chaotically at first, with teachers who abused his voice. At 28, the young Argentine musician took control for good and for the most part on his own. “I worked like crazy, it took me some time hitting my head on the wall, I no longer trusted anyone. After several years of suffering – that gives you a beautiful shell—I entered the profession, in Europe.” The tenor, who refuses nostalgia – “not to deny my roots, only cut the branches so not to suffer too much –is now based in Madrid. “My roots, they are 100% Mediterranean: my grandparents, Spanish, Italian, Lebanese…” "To grind down art because it is in crisis, this is rubbish!”The one who says he is a wild rebel is also a stage animal. “I found some photos of me at the age of 11 that were made in a theater. Finally, I am richer in memories of the stage than off. On stage, I feel at home. But I learn to disconnect quickly. There was no way for me to become a ghost of an actor who trails his roles romantically and finishes in drugs, alcohol, suicide. We, the singers, we do a job, one with some privileges, but one that remains a job, life being something else, a wife, children, and it is much more complicated.” More fragile than other voices, the tenor? “Yes, because it a manufactured voice, not a natural one. Even with the best technique, the best parachute in the world, it is still singing and it is still jumping into the void – and sometimes the parachutist is killed. The singer, as a human being, is not infallible. The important thing is that he gives it all, 100%. We are clowns of luxury, ‘clowns’ in the best sense of the word. A valve to amuse, to help find feelings, to reflect. We are instruments to recreate the music the great masters have created. To grind down art education because there is in crisis, this is rubbish. A society that has a full stomach but no culture, sooner or later it falls.” José Cura builds bridges across history and in particular for his role of Samson, which he has sung for fifteen years, a heroic, difficult role “with its infamous, anachronistic text…” "But music is so beautiful, sometimes kitschy, in the style of the time. But if you take history, three thousand years later, nothing has changed! We continue to kill in the name of religion, whatever the name of god invoked. When I started singing Samson, I fell into the trap of the prophet. Then I discovered he was a judge, a military leader, the leader of the revolution, a provocateur who uses his powers, his strength of conviction to incite rebellion. The text of the Bible is terrible; it's a horror movie full of hatred and blood. In the second act, Samson falls. Behind the man was a woman, Dalila. There are still people capable of endangering the destiny of a country for sex. In the third act, he asks his god for his strength, to become the murderer he was again, a terrorist today. Nothing changed. That's the great lesson of Samson! " Holding most of his roles in the Italian repertoire (his Otello is as legendary as his Samson) Cura also works in French opera but refuses the Wagnerian adventure: “It is a question of language, not voice. Those who live for the music can get it out – phonetically – but if like me you try to live every word, then we do not sing in a language we have not mastered. Even if I do not pronounce French perfectly, I know what I say and that is essential for an actor.” And Cura, who also speaks English, dreams of performing Britten’s Peter Grimes. Meanwhile, in 2010 he will stage his own Samson. “A modern aesthetic, stylish, trying to avoid the kitsch of the bacchanal but without updating the political message.”

|

|

|

|

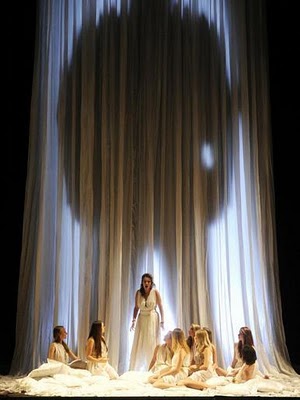

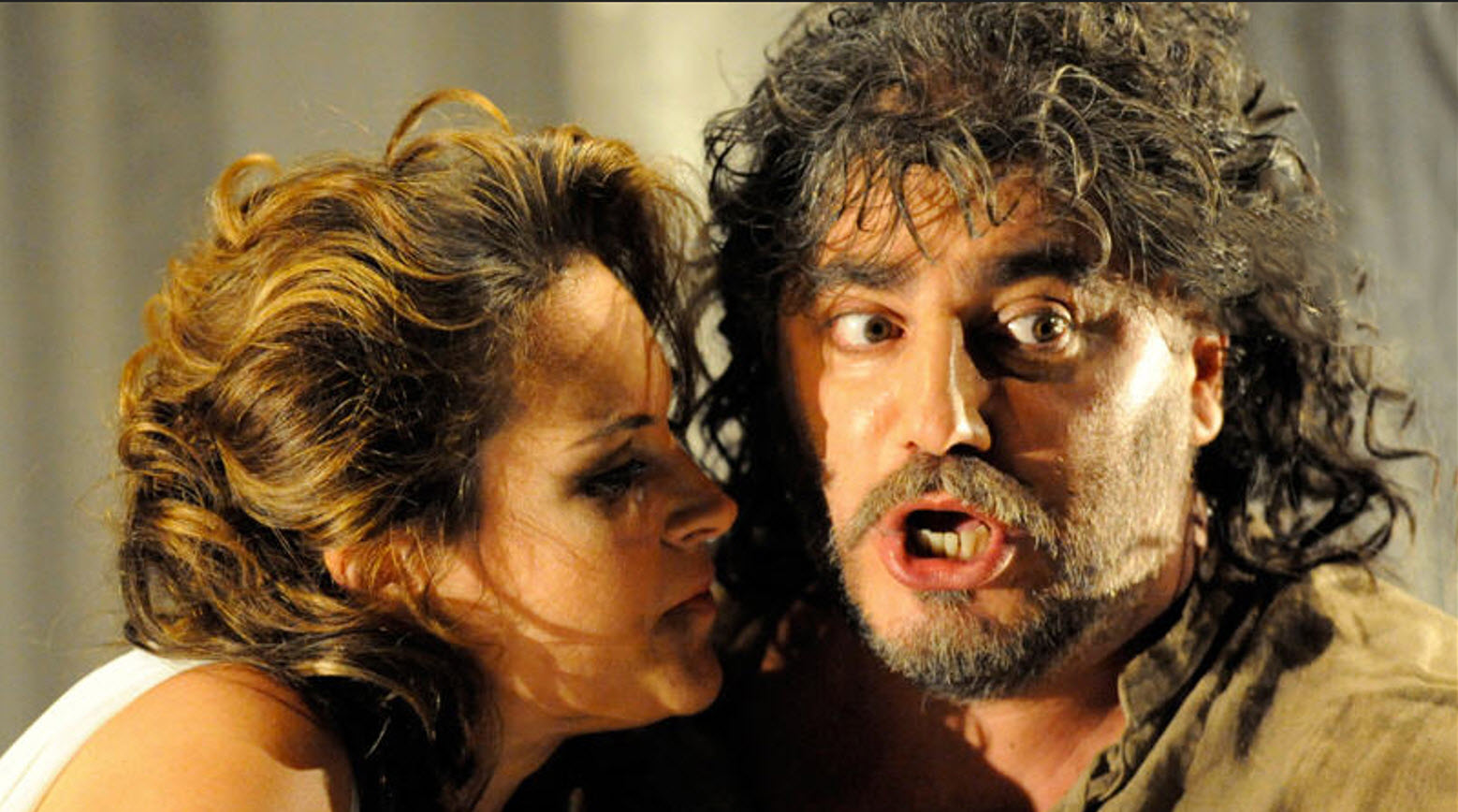

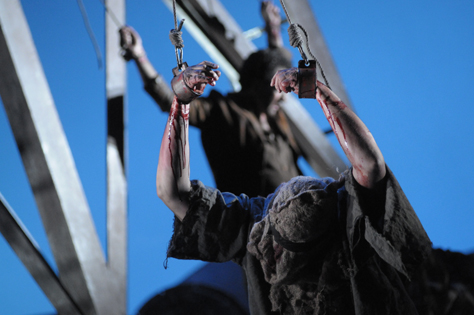

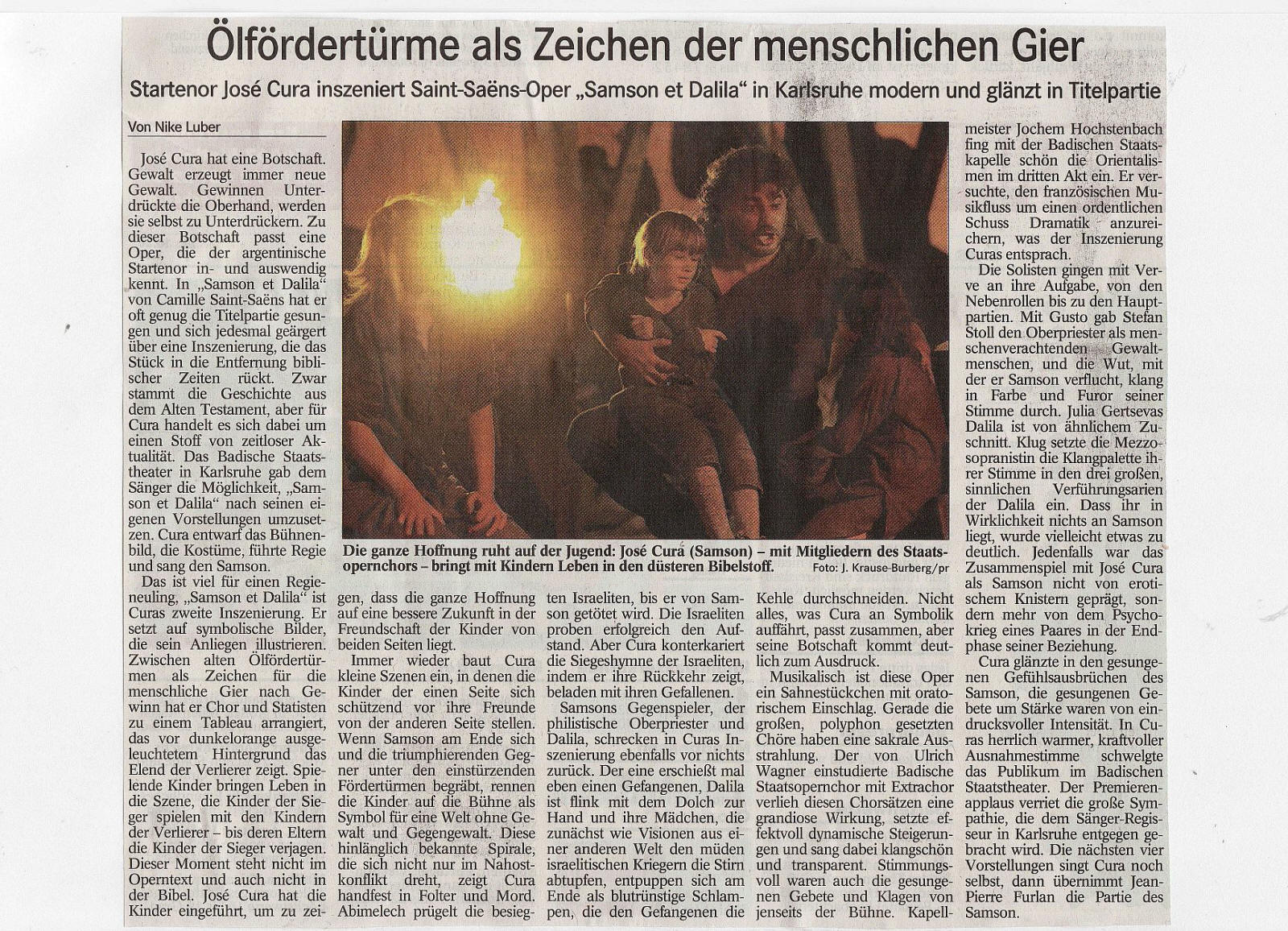

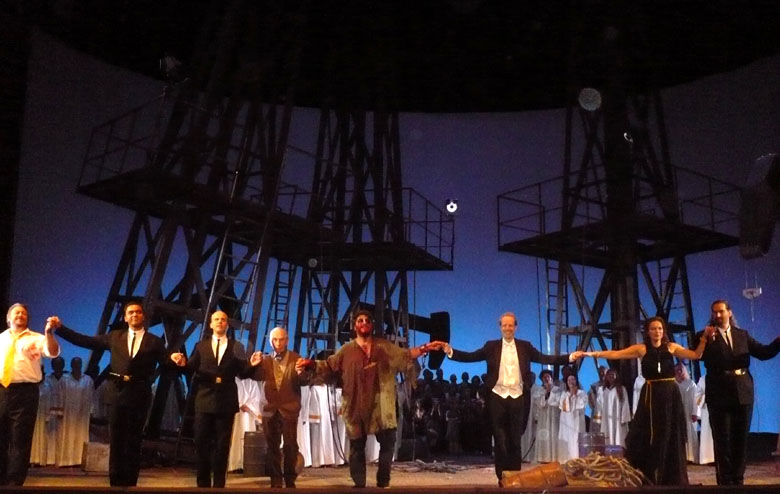

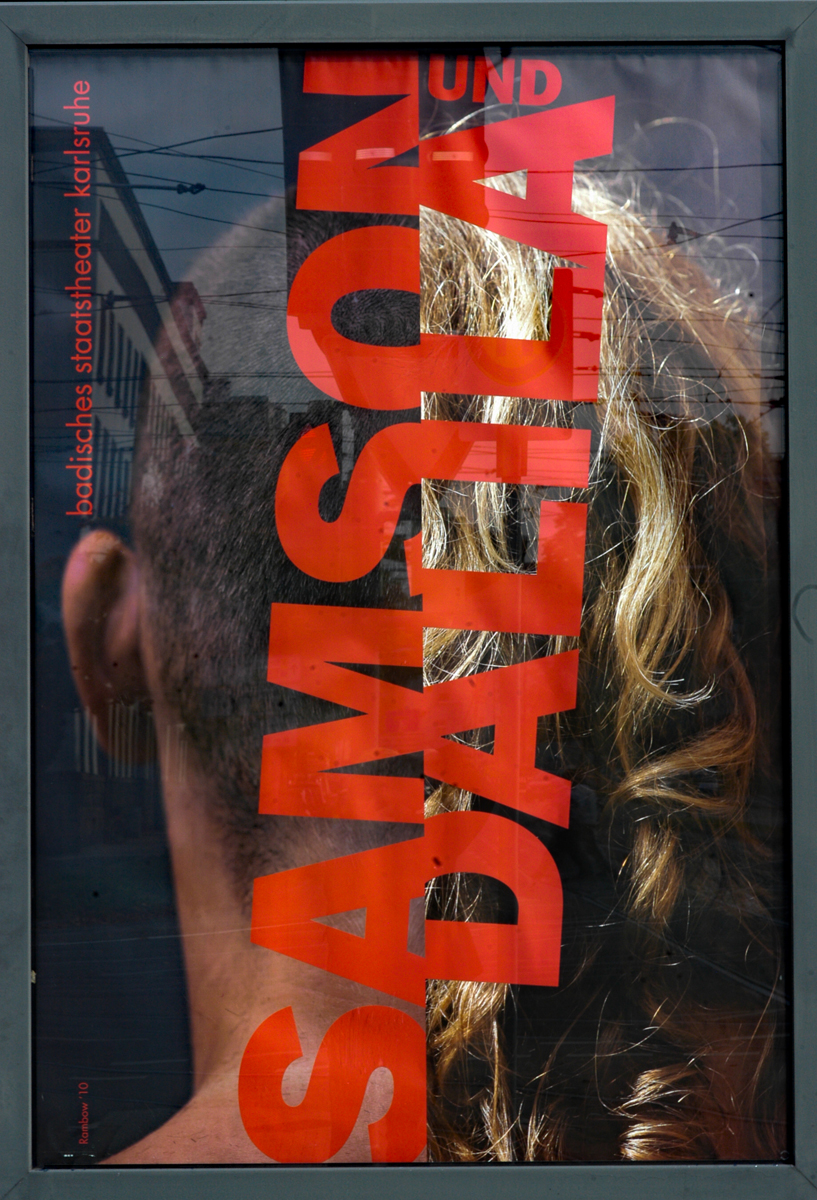

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: “To come to the point right away: Cura knows his job, has mastered the director's craft. What he put on the stage of the Badische Staatstheater made sense. The singer-director offered up an altogether plausible version, which thankfully omitted superficial updating. Cura by no means abstained from referring to the present time; rather, he unquestionably comments on threats with which the world is faced these days. In his view, the themes molding this opera are power and domination, sex, betrayal, fanaticism, and killing driven by religious zeal. Thus, in Karlsruhe there were scenes of violence, brutality and warlike barbarity, of seduction and hypocritical eroticism, in which lust for power, hunger for revenge and unbridled blind passion characterized the actions of the main players. The most hauntingly powerful moment staged was the excitingly intense and sensitively acted seduction and fake love scene, where Samson found himself continually entangled, caught in a white stage-high veil or net--code for Dalila's web of seduction. Cura was brilliant as Samson, with an exquisitely colored, sonorous, in the high notes brightly shining tenor (voice). Moreover, he delivered a highly sensitive, multi-faceted character portrayal, fascinating vocally as well as for his acting.” Rheinpfalz, October 2010

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: “The personal union of director, costume designer and stage designer does not necessarily lead to a successful artistic effort; nonetheless, this evening belonged to José Cura, towering in every respect. And while one does not have to necessarily relocate the story from the Old Testament to the present day (symbolized by three abandoned oil derricks), Cura offered a logical, and quite sensitive interpretation that was still harmonious with the original. The audience celebrated the artist with frenetic applause.” Opera Point, 17 October 2010

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: ‘That was one of the rare opera evenings that are etched on one's memory and you won't forget for your whole life. The first night of Saint-Saëns' opera Samson and Dalila at the Badische Staatstheater ended with standing ovations and was a real triumph for all participants. It is no exaggeration to speak of a great moment of opera, one that will go down in the annals of the top-class Karlsruher Staatsoper. You really don't know where to start with enthusing- best with the super fantastic singers who made the Opera House in Karlsruhe a world stage on this evening. What an exceptional singer is José Cura, whose Samson belongs with the best! With an extremely powerful, expressive, virile, and ideally supported Italian heroic tenor, he drew a convincing portrait of the biblical hero, whom he also gave a convincing profile through his acting. With utmost élan he threw himself into his role which didn't cause him even the slightest difficulties and whose murderous cliffs he mastered with great sovereignty and distinct technical skills.” Der Operfreund, October 2010

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: “José Cura (Samson) was remarkable, portraying his character with tremendous intensity. Masterfully and at all times credibly, his brilliant tenor voice offered insights into the deep psychological depths of his character – transparently and with great sensitivity, he sketches the conflict between unswerving loyalty to God and love for his rival. It was an evening with an outstanding José Cura in every respect. While one doesn't necessarily need to transpose this Old Testament subject into the present (three disused oil derricks) – this production clearly demonstrates that it can still be very coherent with a logical and sensitive interpretation. The audience celebrated the artists with frenetic applause.” OperaPoint 17 October 2010

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: “José Cura has a message: violence always begets violence. When the underdogs prevail they in turn become the oppressors. His message fits this opera, which the Argentinean star tenor knows inside and out. Cura shone when singing the emotional outbursts of Samson, his sung prayer for power were of impressive intensity. The audience of the Badisches Staatstheater reveled in Cura’s exceptional, wonderfully warm and powerful voice. The applause at the premiere showed real empathy between the singer-director and Karlsruhe.” Badisches Tagblatt, October 2010